How Cheney, Rumsfeld, Bush Sr. and Ronald Reagan helped create modern terrorism

I’m in the final months of my dissertation. Damn, that feels good to say. At this point, I’ve cemented all the actual “work†– in other words, my points of originality constituting my actual contribution to the field have already been written out. Now I find myself going back and writing some of the nitty-gritty background information of the early chapters. It’s somewhat arduous in that I might spend an entire day researching minutia for the purpose of simply fact-checking a few paragraphs.

I’m in the final months of my dissertation. Damn, that feels good to say. At this point, I’ve cemented all the actual “work†– in other words, my points of originality constituting my actual contribution to the field have already been written out. Now I find myself going back and writing some of the nitty-gritty background information of the early chapters. It’s somewhat arduous in that I might spend an entire day researching minutia for the purpose of simply fact-checking a few paragraphs.

But it is vital work and I’m not complaining. I mention all this only because I spent the entire day yesterday reviewing the history of the Cold War. It’s one of those quirky time periods for me because I grew up as a Reagan kid – I remember Carter, but only barely and would certainly have had no interest in politics outside of those funny yellow ribbons everyone had wrapped around their trees. All this is to say that the Cold War was more background than impact for me as I developed my youthful political awareness.

Of course, growing up in the Reagan Cold War is like walking into a sporting event at halftime – you know who’s playing, you know the score, and you hear the commentary, but you really have no background on how it all began. The best you can do is ask the guy next to you. Unfortunately, that dude is a die-hard fan of the home-team and you’re only getting a one-sided perspective. To make matters worse, since you’re wearing a home-team jersey, the other folks are rigidly tight-lipped on their perspective – except for the occasional one that decides to throw their popcorn at you.

The point is, I know about the Cold War from history class, from watching the news in the 80s, and insofar as it intersects with my own research. But it has always been difficult for me to contextualize it from its post-WWII origins to its death rattle in the early 90s. I suspect that such contextualization might be even more difficult, at least in some ways, for those who actually lived through a larger portion of this bizarre time period and had to endure decades of partisan propaganda stemming from rank uncertainty.

Having arduously and sufficiently educated myself yesterday, I would save you the pain and say right now that I have no intention of thrusting an extended history lecture upon my unsuspecting readers. However, there is a particular aspect of the cold-war period – somewhere near the year of my birth – that is tremendously important to reiterate for those of you who don’t know or have forgotten: Jimmy Carter could have changed the world were he not thwarted by a concerted propaganda campaign lead by some of the most notorious figures of the “second†Cold War.

Having arduously and sufficiently educated myself yesterday, I would save you the pain and say right now that I have no intention of thrusting an extended history lecture upon my unsuspecting readers. However, there is a particular aspect of the cold-war period – somewhere near the year of my birth – that is tremendously important to reiterate for those of you who don’t know or have forgotten: Jimmy Carter could have changed the world were he not thwarted by a concerted propaganda campaign lead by some of the most notorious figures of the “second†Cold War.

The first Cold War period from the Truman Doctrine through the 60s was a tragic combination of immensely bungled diplomacy, misunderstandings, and territorial pissings lead by two very mistrustful states, each with their own vision of global economic policy in the post-war era. Fast forwarding, the Soviet performance in dealing with Afghanistan (a whooole n’other can of worms) lead many foreign policy analysts to reconsider the extent of Soviet power. Finding influence in the Ford administration, their findings were supported by extensive CIA investigation. This is important to understand because it marked a moment in time where the U.S. administration, backed by a preponderance of hard evidence, was prepared to deescalate the war and enter into a new era of dialogue with the USSR.

Enter Team B, one of the most infamous attempts by military hawks and Republican ideologues to influence the independent assessments of the U.S. intelligence community.  Their primary motive was to bury the policy of détente, started by Nixon/Kissinger and supported by the leadership of both parties. But beyond this, they were the architects of an October Surprise intended to derail the presidential bid of Jimmy Carter in 1976. Despite hard evidence to the contrary, the findings of Team B’s “independent†assessment was that “Soviet leaders are first and foremost offensively rather than defensively minded†and accused the CIA of consistently underestimating the “intensity, scope, and implicit threat†that the Soviets posed to American and global security.

Their primary motive was to bury the policy of détente, started by Nixon/Kissinger and supported by the leadership of both parties. But beyond this, they were the architects of an October Surprise intended to derail the presidential bid of Jimmy Carter in 1976. Despite hard evidence to the contrary, the findings of Team B’s “independent†assessment was that “Soviet leaders are first and foremost offensively rather than defensively minded†and accused the CIA of consistently underestimating the “intensity, scope, and implicit threat†that the Soviets posed to American and global security.

According to historian Ann Hessing Cahn, “With the advantage of hindsight, we now know that Soviet military spending increases began to slow down precisely as Team B was writing about an ‘intense military buildup in nuclear as well as conventional forces of all sorts, not moderated either by the West's self-imposed restraints or by the [Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT)]' … But even at the time of the affair, Team B had at its disposal sufficient information to know that the Soviet Union was in severe decline. As Soviet defectors were telling us in anguished terms that the system was collapsing, Team B looked at the quantity but not the quality of missiles, tanks, and planes, at the quantity of Soviet men under arms, but not their morale, leadership, alcoholism, or training.†(emphases added)

The motivation of Team B to derail the accurate and bipartisan assessment of the Soviet threat was somewhat understandable in the context of its main players. Of course, the movement began with policy critics, such as Albert Wohlstetter, who constituted the key academic figures of early neo-conservatism. Most of Team B’s supporters, however, held an economic interest in military spending, such as Bechtel president George Schulz, or a political interest, such as CIA Director George H. W. Bush, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, and advisors Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle. Sound familiar to anyone?

In terms of Cold War policy, Team B represented no less than a coup d’êtat. Armed with the politics of fear, that they were demonstrably wrong factually mattered little. Carter was out, Reagan was in, and the 80s marked a dramatic escalation of hostilities, both cold and hot, known in International Relations circles as the ‘second†Cold War.

In terms of Cold War policy, Team B represented no less than a coup d’êtat. Armed with the politics of fear, that they were demonstrably wrong factually mattered little. Carter was out, Reagan was in, and the 80s marked a dramatic escalation of hostilities, both cold and hot, known in International Relations circles as the ‘second†Cold War.

The tragedy of this turn of events is enough to make me wonder what might have been different had American citizens been sufficiently educated, had they been patient and receptive to the voice of reason, had they more vocally asserted their desire for a peaceful solution. Sure, there’s the obvious benefit that we may have avoided Reagan-omics, a dramatic deficit, another decade of fear, nuclear proliferation, Star Wars, ad nausea. But I think the implications go far beyond that.

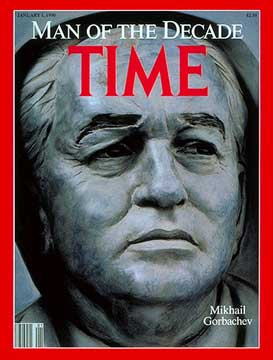

Consider a world where Cold War hostility ended in the 70s. A world where we focused our efforts on the spirit of cooperation instead of conflict. Where we learned to respect the diversity of economic framework and retained the moral high ground from which to demand democratic reform within totalitarian Russia. Could we have avoided the Soviet collapse, an event much lauded by the Right that has resulted in incalculable suffering and poverty in the region and around the world? After a series of old and ineffective Soviet Relics passed through the leadership, might Gorbachev’s reformist policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) have enjoyed the benefit of economic security instead squandered on a pointless Reagan-era arms race? Might such a peaceful transition to demo cracy and a focus on human rights have stood more of a chance of success?

cracy and a focus on human rights have stood more of a chance of success?

Perhaps in the context of such a transition, the Soviets may have enjoyed more resources to ensure either the tenacity of their union or, if collapse was in their destiny the means with which to ensure a smooth transition. Surely a more orderly process could have provided a hedge against the resulting failed states who suddenly found themselves thrust into poverty and chaos. The same failed states who even the Bush White House acknowledge constitute the single greatest threat in securing loose nuclear material and Cold War munitions. Not to mention the human capital of, for example, unemployed and starving nuclear scientists.

Preventing the same material and munitions from now finding their way into the hands of terrorists and rogue nations.

There is virtually no end to the implications that a pre-Reagan peace could have had on today’s world. Of course, none of this will ever be anything but counterfactual since we, the American people, weren’t allowed the benefit of choice. And we were deliberately and systematically denied that choice by a group of ideologues who manipulated intelligence and used blatant lies to formulate vicious, partisan attacks in order to drag this country into war. The very same lying ideologues who, six years ago, were once again put in charge of our national security. And we’ve seen how well that’s turned out.

Yup, history’s a bitch. Especially when we don’t bother to remember it.

Comments

Excellent

Thanks for the reference